Let me just warn you up front, this is not going to be a very exciting post. Packaging is pretty boring. Nor is there anything original about it. I’m using a technique I first read about in articles by Ted Pattison back in about 2007. If I could still find those articles, this would be a very short post pointing you to them, but I did some rooting around looking for them and didn’t have a lot of luck, thus this post.

If you’re just writing a JavaScript solution for yourself, and you only want to use it on a limited number of sites, you may not need to do all of this. You could just write your JavaScript and then modify your master page to import it. But if you’re writing a plug-in for SPEasyForms for instance, you may have some timing issues to contend with to make sure you don’t try to use SPEasyForms before it’s loaded and initialized. Some day I may write a blog post addressing those issues, but this post is going to lay the ground work for developing an SPEasyForms plug-in as a no code sandbox solution that could later be installed and used by anyone, hopefully on SharePoint 2010/2013 or Office 365.

So first, there are a lot of ways to do this. You could use something like WSP builder, which reduces the tedium of doing SharePoint solutions quite a bit. You may even be able to use the SharePoint project templates built into Visual Studio 2013 (or available as extensions for 2012, but I haven’t found a way to get them not to include/deploy the assembly; I may just not have looked long enough). I’m sure there are other ways. If you already know one of them that you like, read no further. But in the end I decided that I wanted no external dependencies. I use Visual Studio 2013 Ultimate, and the SPEasyForms solution is a VS2013 solution, but the build is actually just a batch file calling makecab.exe so Visual Studio is not actually required.

So first, there are a lot of ways to do this. You could use something like WSP builder, which reduces the tedium of doing SharePoint solutions quite a bit. You may even be able to use the SharePoint project templates built into Visual Studio 2013 (or available as extensions for 2012, but I haven’t found a way to get them not to include/deploy the assembly; I may just not have looked long enough). I’m sure there are other ways. If you already know one of them that you like, read no further. But in the end I decided that I wanted no external dependencies. I use Visual Studio 2013 Ultimate, and the SPEasyForms solution is a VS2013 solution, but the build is actually just a batch file calling makecab.exe so Visual Studio is not actually required.

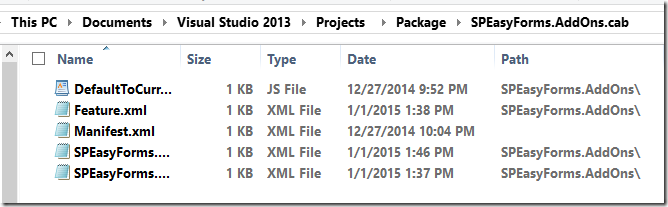

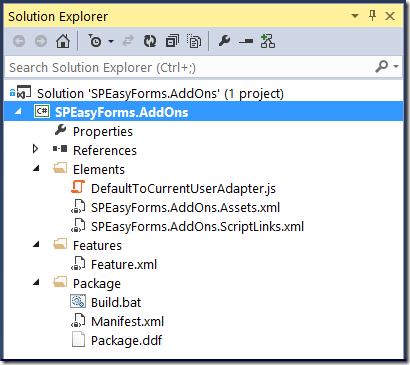

My Visual Studio project for SPEasyForms.AddOns looks like the picture to the left. There are 7 files in it, and I’m going to talk about each of these files individually below except one, the DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js file. This file will be the actual plug-in, and fleshing it out will be the subject of my next blog post on adding a field control adapter to SPEasyForms. For now, this could be an empty JavaScript file, or maybe just have a hello world type alert just so you know it is working after deploying the solution to a SharePoint site collection. The rest of the files are all packaging (i.e. the subject of this post).

I’m going to start from the bottom up with the element files. If you’ve been doing any kind of SharePoint development for a while, I hope these look somewhat familiar. The Visual Studio tooling for SharePoint has come a long way, but you still can’t do much without occasionally manually mucking around with element files. However, this tooling has come to hide many of the details of packaging solutions from you, which is why I felt this post was necessary. The first element file is SPEasyForms.AddOns.Assets.xml, which looks like:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Elements xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/sharepoint/"> <Module Name="SPEasyFormsAddOnsAssets" Url="Style Library/SPEasyFormsAssets/AddOns/2014.00.01"> <File Path="DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js" Url="DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js" Type="GhostableInLibrary" IgnoreIfAlreadyExists="True" /> </Module> </Elements>

This file has a single element, which is a module. Modules are just a way to declaratively add one or more files as content to the SharePoint site where your feature is being installed. In this case there is only one file in the module, the JavaScript file that will contain my plug-in. And I’m putting it in the site collection style library in the folder SPEasyFormsAssets/AddOns/2014.00.01. Note that I included a version number in the path. The reason for this is that once SharePoint has laid down a module file, it will not update it even if you install and activate an updated solution/feature, so when I do want to upgrade my feature I’ll change this path to install the JavaScript in a fresh spot. Another advantage of doing it this way is that it gets around browser caching, which otherwise could cause some of your users to continue using the old code even after an upgrade for some period of time.

The other element manifest is SPEasyForms.AddOns.ScriptLinks.xml, which looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Elements xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/sharepoint/"> <CustomAction Location="ScriptLink" ScriptSrc="~sitecollection/Style Library/SPEasyFormsAssets/AddOns/2014.00.01/DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js" Sequence="57401" /> </Elements>

This file also has a single element, which is a CustomAction. Custom actions in SharePoint allow you to declaratively add things like a button on the ribbon. In full trust solutions, they can also be used to add links to the site settings page or a list settings page or to replace a delegate control. In this case, my CustomAction is a ScriptLink, which cause SharePoint to load a JavaScript file on every page load. The ScriptSrc value tells SharePoint which JavaScript file to load. The other import attribute is the sequence attribute. This tells SharePoint the order in which ScriptLinks should be loaded if there are more than one. You’ll see a lot of examples on the Internet using the number 10000 for the sequence. This is because Microsoft reserves numbers below 10000 for it’s own purposes. I tend to use higher numbers. If you use a number between 57400 and 57700, I guarantee your script will be loaded after SPEasyForms is loaded, and before it does its work (which is what you want if you’re writing a plug-in, you need $.spEasyForms to be defined, and you need to insert your plug-in before $.spEasyForms.init() is called). I don’t believe it will cause any problems if two or more ScriptLinks use the same sequence number. It just results in the scripts being loaded in an indeterminate order, so they better not be dependent on each other.

The next file is the Feature.xml file, which just binds together all of the files which will be part of our Feature. It also assigns a unique id (GUID) to the feature, and a title and description. In our case it is just bringing in the two element files described above and our JavaScript file, and it looks like:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Feature Id="83d6bab2-b101-4816-bdbb-6ba82f3b03b0" Title="SharePoint Easy Forms Add-Ons" Description="Default to current user adapter." Version="1.0.0.0" Hidden="FALSE" Scope="Site" xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/sharepoint/"> <ElementManifests> <ElementManifest Location="SPEasyForms.AddOns.Assets.xml" /> <ElementManifest Location="SPEasyForms.AddOns.ScriptLinks.xml" /> <ElementFile Location="DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js" /> </ElementManifests> </Feature>

The other thing to note is that this feature is scoped to site, which makes it a site collection feature. I generally make all features in sandboxed solutions site scoped, because the way sandboxed solutions are upgraded makes web scoped features a bit of a nightmare.

The last XML file is the Manifest.xml, which just assigns a unique id (GUID) to the solution and tells SharePoint where our one and only feature resides:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <Solution xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/sharepoint/" SolutionId="eec95124-c174-4cf2-9978-25a37d3375a8" > <FeatureManifests> <FeatureManifest Location="SPEasyForms.AddOns\Feature.xml"/> </FeatureManifests> </Solution>

.OPTION Explicit .Set DiskDirectory1="." .Set CabinetNameTemplate="SPEasyForms.AddOns.wsp" Manifest.xml .Set DestinationDir="SPEasyForms.AddOns" ..\Features\Feature.xml ..\Elements\SPEasyForms.AddOns.ScriptLinks.xml ..\Elements\SPEasyForms.AddOns.Assets.xml ..\Elements\DefaultToCurrentUserAdapter.js

@echo off makecab /f Package.ddf pause

cd ..\..\Package Build.bat $(ConfigurationName)